Money Mule Accounts: We Need to Shut Them Down

Money mules fuel scams and account takeovers. UK data shows how banks and fintechs must act faster to detect, block, and stop money mule accounts.

This article is about money mules in the UK, but it is probably representative of any country. So, listen up. Money mules are one of the biggest reasons that transnational organized crime is successful in account takeovers (unauthorized transaction) and consumer scams (authorized transactions). Banks, credit unions, fintechs, and Banking-as-a Service solutions are generally weak when it comes to detecting, blocking and removing money mules. And in some countries, in the interest of preventing debanking of the vulnerable and the young, money mule accounts are not even shut down.

In August, the Financial Times reported: “More than 225,000 people (in the UK) were identified as ‘money mules’ for letting criminals use their accounts to launder funds last year”. The FT story went on to report: “The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) said it recognized the scale of the challenge in tacking the fast-growing problem of money mules and their pivotal role in enabling the rise of fraud (in the UK)—which rose to a record 45 percent of all UK crime in the year to March.” The FCA also said the “largest UK banks closed 226,957 money mule accounts . . . up from 184,935 a year earlier.”

And with all of these closures, there are probably still hundreds of thousands of undetected money mule accounts waiting to receive/move fraud and scam money.

To help provide more analysis to this issue of money mule accounts, the UK’s Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) just released a report, Following the Fraud: The Role of Money Mules. The authors, Kathryn Westmore and Allison Owen, were given money mule data by Lloyds Bank from June 17 2024 – August 11 2024 for this analysis. The data is based on money mule accounts at Lloyds Bank.

One of the first things that was identified was that as the money left the Lloyds’ money mule accounts, the money transferred to a few other financial institutions. In fact, RUSI reported: “38% of the payments by total value went to just three banks/ payment firms, with 20% of all payments by total value going to one single firm. This firm also received the highest number of payments from money mule accounts. These three institutions can be characterized as digital financial institutions, offering banking and money transfer services via apps and online banking.” RUSI also reported that that “over 450 (10%) of the payments identified from mule accounts went to Banking-as-a-Service providers—a disproportionate share compared with the overall share of Faster Payments to these services.”

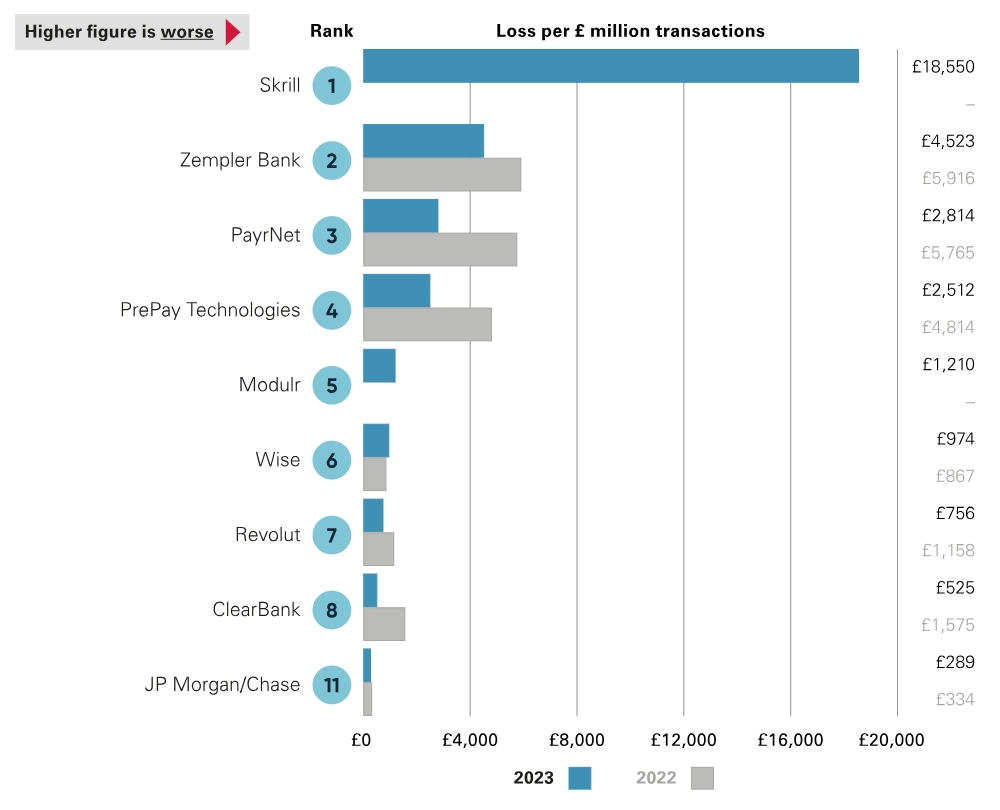

In 2024, the Payment Systems Regulator detected a similar issue with a concentration of money mule accounts in smaller receiving banks and payment firms and also more activity in certain larger receiving banks (directed PSPs) in 2022–23. Charts 1 and 2 show the PSR assessment. Note: non-directed PSPs are smaller financial organizations.

Chart 1 – Value of APP scams received per £ millions of transactions Non-directed PSPs

Chart 2 – Value of APP scams received per £ million of transactions Directed PSPs

The PSR September 2024 consultation document also showed “that non-directed PSPs accounted for just over 8% of all Faster Payments made in 2023, but received 53% of all fraudulent transactions,” There has not been an update by the PSR since 2024, but it seems clear that some financial institutions may be still be weak at eliminating money mule accounts.

An obvious issue with the bank customer becoming complicit in making accounts available for money muling is highlighted by this quote in the Financial Times article. Ben Donaldson, managing director for economic crime at UK Finance said “many money mules were tricked or coerced into it without knowing it is a crime for which they can be imprisoned, even though few are convicted. I don’t think we can say all mules are victims but certainly many mules are victims.”

So, there are two key issues: 1) a certain number of banks need to be much better at detecting money mule accounts, and 2) how to deal with customers (maybe the young and foolish, maybe victims of scams themselves, and maybe those looking for fast money) who make their accounts available.

The RUSI report also identified the age of the mule accounts, which supports the ‘selling of accounts’. “20% of known money mule accounts were older than five years, with the majority (about 60%) being older than one year.” The ‘older’ aspect of these money mule accounts is symptomatic of the current customers selling the use of their accounts. This can make it more difficult to detect money mule accounts.

Another interesting observation is the short amount of time the money stays in the money mule account. The RUSI study showed: “nearly 28% left the account within 15 minutes and a further 25% left within an hour. Less than 15% of the money remained within the accounts after 24 hours.” This highlights the need for strong anomaly detection on inbound transactions so that suspicious money mule transactions can be identified and a hold can be quickly placed on the account to prevent the funds from moving. The UK has laws that allow suspicious transactions to be held. Other countries may need to add such ‘immediate hold’ laws.

Part of the money mule control should also be looking at fast exfiltration from the account. The RUSI report shows money can exfiltrate from the money mule account via transfer to another bank account, via ATM cash withdrawal and via debit card transaction. Figure 1 from the RUSI report contains detail of the exfiltration activity.

Figure 1 – Share of Payments Out of Money Mule Accounts, by Types

Another interesting point is the large amount of small dollar transactions exfiltrating from the money mule account. The average payment amount was £532. And the average debit card transaction was £107. This is consistent with reports that one-quarter to one-third of APP scam losses are less than £100. These small amounts will be more difficult/problematic for anomaly detection systems to pick up.

Actions to Take from the RUSI Money Mule Study

This report can help a financial institution undertake a strong money mule management program. Here are some of the key data points to take into account when building this program.

- Any account, regardless of the age, can be a money mule account. Current customers are being solicited to share their accounts for a fee. When the economy is tough, this can be enticing.

- Money mule activity is not just about large dollars. In fact, as this study shows much of the transaction activity is low amounts, around £1-500. How to deal with a high volume of small amounts can make the money mule solution more difficult. And a volume of small amount transactions into a mule account may look more normal.

- When analyzing the outbound activity of a suspect account, look at receiving bank to see if it is anomalous (e.g. many transactions from multiple accounts going to a new fintech or to a small receiving bank). Also take into account the other ways to exfiltrate the money (wire, debit card, ATM) as part of the outbound analysis).

- Because the money leaves the money mule account quickly, it is important to be able to complete a quick risk assessment of the inbound transactions.

- Track and report the accounts the money is transferred to from your bank to the next receiving bank (outbound from your money mule account to a new money mule account). This is valuable information for FIs.

A special thanks to Lloyds Bank and RUSI for providing the money mule data and the analysis. It helps to provide some keen insight to money mule accounts and the associated money movement. An interesting follow up for RUSI would be to analyze how long a money mule account was active and how many times it was used as a money mule account before it was shut down. This report also highlights how if there was more data sharing between financial institutions, we could help to weaken the value of money mules as a way to stop account takeovers and scams.